by J.B. Stevens

Robert Forsyth’s heart longed for Scotland. The American Colonials spoke with an odd accent, their manners were disgusting, and the food was ghastly. Despite the challenges, they’d become his people. Their love of freedom and indomitable spirit was overwhelming. The United States was his true home. This new nation gave him everything. He was proud to serve her.

The War for Independence was a test of will, and he had passed. Unfortunately, there was a price, the foul dreams never relented. Musket balls passed nightly, and he woke in a sweat. He paid it no mind—his impacted British flesh, and the redcoats always missed, and the morning always came.

It was his duty to control his emotions. Even on that sad day when he left the Revolutionary Army, he did not express regret. He treasured his service in Lee’s Dragoons. General Lighthorse Lee was a fine man and an outstanding leader.

As a departing gift, Lee had commissioned a portrait of Forsyth. The painting now hung above the fireplace in his Augusta, Georgia, home. Forsyth’s wife said the painting made him look dashing, taller than the average man, with sharp features and light eyes.

Life in Augusta was pleasant. The missus kept the home and looked after the boys. Often, when gathered around the hearth fire, Forsyth told them of the uprising, the Declaration of Independence, and the formation of their Republic. He swelled with love. Providing for his family was a mystical blessing from the Lord.

After a spell in Virginia, he accepted General Washington’s post as U.S. Marshal for Georgia. Forsyth was honored to be the Federal Marshal—a fledgling government needs volunteers willing to chase down evil-doers.

Forsyth enjoyed hunting men more than he cared to admit.

It was a hot day when the court issued a civil summons for Beverly and William Allen. The brothers were using the Methodist Church as a vessel for grift. Illegal and immoral.

Forsyth accepted the judicial document and set off after the pair. He tracked them in the night. The evening was cool as fall in the highlands, and crickets chirped. The blue coat scratched his neck, and he inhaled the scent of damp wool.

Forsyth located the renegades at a cabin outside Augusta, in an evergreen forest. He came to the entrance and knocked but received no answer. The latch sat unsecured.

Forsyth pushed the timber door open. A group of men were playing cards and drinking ale.

“United States Marshal,” Forsyth said. “I’ve come to serve process upon the Allen brothers.”

He listed and feet stamped, and doors slammed, and bandits scattered like so many cockroaches startled by an oil lamp.

“Brothers, let us speak outside and avoid any ill-will,” Forsyth said to the now open space.

He received no answer.

Forsyth looked back at his deputies. Two hard young men, veterans of the Potomac and residents of neighboring plantations.

Forsyth nodded and pulled his cap and ball pistol. Looking at the confined space, he replaced the weapon and drew his saber. Oiled steel glinted in the lamplight and the leather wrap handle felt familiar in his hand. They edged into the tobacco-smoke-filled room, hunting their query.

“Allens, men, come forth. This is a small matter that does not need to become a large one,” Forsyth said.

The house was still. Forsyth heard a cow groan in the back field.

The younger deputy, a high-strung man of fine stock, grinned. “We search?”

Forsyth nodded. “We do.”

The first floor was simple. Four pine-wood chairs, an armoire, and a table. Two men, not the Allens, presented themselves near the kitchen. They claimed to have no idea where the brothers hid.

The root cellar was cool, and the earthy smell so thick Forsyth could feel it in his mouth, and as empty as King George’s tomb.

The older deputy looked up. “The second floor?”

“Indeed. Now, lads, we must respect the high ground. Go gentle,” Forsyth said.

Forsyth led with the blade. The first bedroom door was unlatched.

“Let us not make this into real trouble,” Forsyth said into the dark. “Brothers, can we speak outside?”

No answer.

The deputies searched the room. A young woman of questionable repute wearing enough clothing to be better off nude hid under the bed. No doubt the men’s entertainment.

The three lawmen came to the second, and final, bedroom door. It was latched and secured.

The moment had arrived.

Forsyth knocked. “Allens, open at once.”

There was a click.

A musket shot came. It was loud—more so than in the dreams, closer than the ones from the war.

Wood splintered and he smelled char, and he felt heat near his right eye but no pain. A flame burned in a far-off place.

He tasted burnt gunpowder and heard a wail. As he fell, the deputies slammed through the door, riding a cloud of purple mist. There was more gunfire, but the sounds faded, and the mist grew and Scotland came through the purple and he saw his mother.

Behind her stood his sons, somehow grown, and they appeared well and godly.

He walked to his mother, hugged his grown sons, and entered the home of his birth and the door closed behind him and the latch rested—secure.

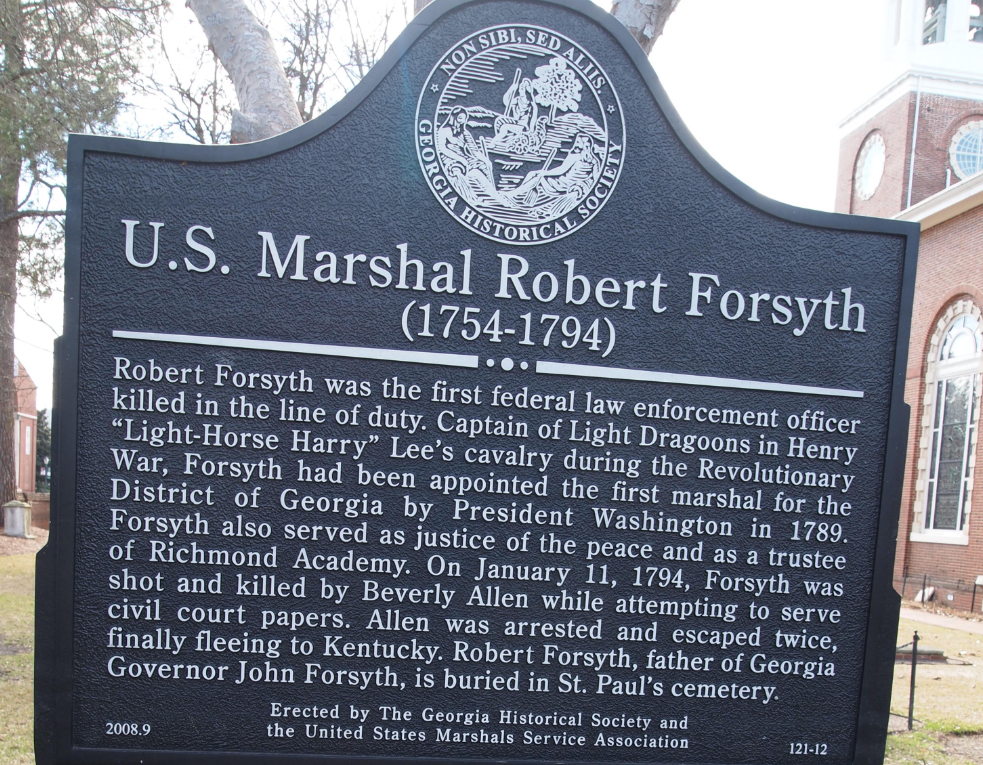

Bio of Robert Forsyth (as it is a true story, this feels necessary)

U.S. Marshal Robert Forsyth was born in Scotland in 1754. He immigrated to the United States and enlisted in the Continental Army at the start of the Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of Captain. After his war service, in 1785, he moved to Augusta, Georgia—where he established himself as a community leader.

President George Washington appointed Forsyth as the U.S. Marshal for Georgia on September 26th, 1789—one of the original thirteen U.S. Marshal appointments. On January 11th, 1794, U.S. Marshal Forsyth went to a home to serve civil papers, a duty still filled by the U.S. Marshals Service. While attempting service, Forsyth was shot and killed. He was the first federal law enforcement officer killed in the line of duty. He was forty years old and left behind a wife and two sons, one of whom later became the Governor of Georgia—John Forsyth.

Forsyth is buried in Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church Cemetery in Augusta, Georgia.

J.B. Stevens lives in the Southeastern United States with his wife and daughter. His war poetry collection, The Explosion Takes Both Legs is available from Middle West Press. His short story collection, A Therapeutic Death is available from Shotgun Honey Books. His pop poetry collection, The Best of America Cannot Be Seen is available from Alien Buddha Press.

For a free collection of his short stories, go to jb-stevens.com.